The Doric Temple¶

This is a working translation (and in part summary) of Max Raphael's 1930 book Der Dorische Tempel. The translation, commentary and new illustrations are made by Jules Schoonman as part of his PhD research on Max Raphael's writings on architecture.

The text contains three types of footnotes: by Max Raphael from the original edition, indicated by ^MR, by the editors of the Suhrkamp Werkausgabe, indicated by ^WA, and new ones by Jules Schoonman, marked by ^JS. In the source code of this page, the numbering of the footnotes in the original edition is preserved.

Existing headings have been abbreviated and new ones have been added for clarity and ease of navigation. Some of the editorial changes in the Werkausgave have been reverted to stay true to the original structure of the publication.

Translator's notes have been added with either critic markup or [between brackets].

Dedicated to my students at the Volkshochschule Groß-Berlin in memory of collective work.1

Motto:

For who can see the comings and goings of a god, if the god does not wish to be seen? (Odyssee, X 573)2

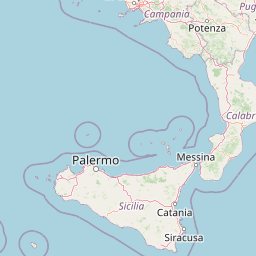

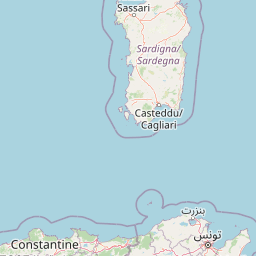

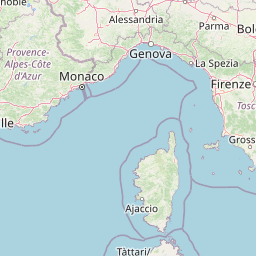

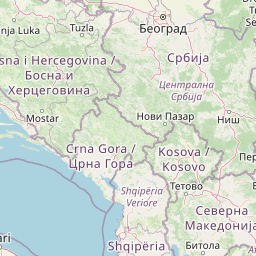

After visiting Milan in 1926 Raphael returns to Italy in 1928 to visit Rome, Napels, Paestum (February 28) and Sicily (from March 10). Although his plan is to continue to Athens, he decides to return early due to exhaustion. During his 1928 trip he visited and measured 12 temples spread over four archaeological sites, indicated by the colored markers on the map.

List of illustrations:

- Paestum, Poseidontempel

- Paestum, Basilica

- Akragas, Junotempel

- Akragas, Concordiatempel

- Segesta

- Athen, Parthenon

- Selinunt, Tempel

- Samos, Hera sculpture

Foreword¶

The intellectual history of Christian Europe is to a large extent an exchange [Auseinandersetzung] with Jewish-Greek-Roman antiquity. Overlooking the influential representations (myths) that have been formed about 'the' essence of 'the' Greeks, a distinction can be made between those concerning content, form and method. It is obvious that the last one is the hardest to recognize since it most powerfully penetrates ungreek matter with greek spirit. It nevertheless represents the highest and most valuable examination of Greek spirit. In each epoch, the three either run parallel or in succession, whose order is being determined by a multitude of factors. Of the youngest myths, the last two lingered most strongly in the consciousness of the educated layman: the classicist (Winckelmann, Lessing Goethe) and the romantic (Burckhardt, Nietzsche, Bachofen). The first was mainly formalistic; the second content-based. Both were closely related to the formation of civil society; it remains to be seen whether they supported its revolutionary or reactionary tendencies. If I am correct, a new myth is currently forming among the intellectual avant-garde (Le Corbusier, Strawinsky, Picasso, Valéry). Its cultural-historical form and purpose cannot yet be overseen. Without disregarding historical patterns and relations, it will significantly depend on which forces still come into play.

This work consciously aims to contribute to a new Greek renaissance. It deliberately selects the temple of Poseidon in Paestum as the object of study. On the one hand in opposition to the classicist myth, which could only appreciate the 'terrible style' of this completely foreign world with the help of art history (Goethe: Italian Journey, Naples, March 23), as well as to the romantic one, which overall neglected the visual arts compared to sociological and religious factors. Then, above all, in recognition of architecture as the universal art and of the temple's realism3 in conscious contrast to all the idealistic phases of Greek history and our own past. Not only the simultaneous universal and realistic object of study, but especially the investigative method aims to direct the the new myth. It is based on the exclusion of any developmental history and completely based on a science of art rooted in a theory of creation, whose task is first the factual documentation of the work of art [Festlegung des künstlerischen Tatbeständes], and second to assign to, or, better, derive from the empirical evidence a clear and comprehensive world view.4 Since a science of art is lacking, we have to work out its method through the examination of individual works of art.

I will first discuss the design of the building and the space, subsequently the idea, that is the world view, which is expressed by this design.

Design of the Doric temple¶

Building mass¶

Each building mass [Baukörper] has three main characteristics:

- Extension [Ausdehnung]

- Matter [Materie]

- Energy [Energie]

Extension it shares with any geometrical body. Its shape [Figur] is an encounter of places, which divides the total space in enclosed (and designed) and excluded (and undesigned) spaces. The second characteristic matter it shares with all physical bodies. It doubles the aforementioned border (between in- and outside) and allows to distinguish between outer and inner form. The third, energy, is closely related to the second and is the play of forces, loads and supports, shearing force, buttresses, etc. The building is therefore the materially and energetically realised composition of places, which defines, as a boundary, the enclosed space and its connection it to the exterior. The design of the border will further determine the connection or division between both spaces.

This definition is too indeterminate, as it would fit any object [Körper], including a plastic one. Only the study of its concretisation and relationships provides the right nuances to understand Doric buildings as an architectural and not, as often falsely assumed, plastic object. For now the definition is sufficient however to familiarise us with the character of these elements in the Doric temple.

Geometric figure¶

a) Fusion¶

The Doric Tempel is a unified building: the compositional fusion of two different shapes. A parallelepiped [of planes and right angles; cuboid] and a prism [of planes and non-right angles] are fused into a shape whose front exists of 5 sides, and the total volume of 7 layers. The first is the (quantitive) foundation, the other the (spiritual) crown. The fusion is achieved by (1) the diagonals, which across the stepped corners reach into the Pteron [peristyle] and further into the Antenfront5, the (2) inward upward movement (the stepped corners, the tapering and slanting of the columns and beams) and (3) by the ridge connecting both pediments, parallel to the depth axis.

A comparison with the simpler volumes of the Egyptian pyramid, and assembled volumes of the Christian church provides a better understanding of the Doric Temple as a unity composed of two opposite parts. In the pyramid, four coherent and unarticulated planes lean toward each other until they converge into four borders and a point. Each of the slanting surfaces becomes an isosceles triangle. Even greater is the geometric simplicity of the Colosseum, where the oval shape determines the articulation of the upper floors, and is not replaced by another figure. In contrast, the Romanesque church is assembled of multiples cuboids stretching in all three directions. Here, the assembled geometry is based on a transcendental and religious view: the shape of the cross.

b) Proportion¶

The opposite elements, fused into a unifying figure, were proportionally linked for the Greeks. 12 temples6 of greater Greece fall into two geometric categories7. The geometric limitations match those of Greek tragedy and the few principles of Presocratic philosophy. For the group of larger temples, the Stylobat measures Greek foot, and the height of the columns is foot. For the smaller temples, these measurements are , and . The Greek foot measures either (for example at the Poseidontempel) or (for example at the Juno and Concordia tempel in Akragas). All deviations can be explained on the basis of the individuality of the artistic conception, which materialised in the building.

Arranged by size, the order of the dimensions is as follows: depth, width, height. The earthly dimension of eventsNot clear and their equality – which cannot even be escaped by a movement of the head – is the axis for the relationship to the other dimensions. Often the ratio between the depth and the width of the Stylobat is close to the golden ratio, and relate to each other like the small part to the whole []. And often the overall height [of the pediment] is the greater part of the subdivided smaller part [ subdivided into and ; the column height is . The width is the small part of the depth, and the height of columns is the small part of the width. The pediment tip is .] The golden section plays an important part in the Doric Tempel both for the line segments and the angles, in the approximations and and .

[]

[]

Its characteristics are: (1) it creates a relationship between unequal parts which also expresses their relationship to the whole structure, (2) it balances static and dynamic divisions. It therefore is an immanent, all-round, design-determining proportion.

c) Finiteness¶

This is why the Doric building is finite and conceived for a finite eye. The entire architectural organism is contained between the depth-movement of the sides and the width-movement of the fronts; between the ascending stairs and descending roof. The movement is closed within itself, not from the outside; it becomes a being. All it is can be seen, although not in its being but in its effect. The varying intercolumniation, the asymmetries between both fronts and sides, and within individual fronts and sides, are only visible with a measuring stick and not instantly to the eyes. The entire artistic meaning depends on their indirect effect: the liveliness in repeating the same. The building in its finiteness is not just rational, but the irrational moment is organically encapsulated in its creation according to its substance (genesis eis ousian)8.

d) Constancy¶

The Doric Tempel is a constant building volume. It cannot be prolonged, widened or elevated without reconsidering the inherent laws of all dimensions in their totality. Within this constancy, and closely connected to it, one can locate an objective and subjective reality. The first consists of the probable ever increasing differentiation of the intercolumniation of the front and sides. Even after switching to contraction this was not completely abandoned. Still at Segesta, the centre intercolumniation of the temple’s front is not of the same size as the normal intercolumniation of the sides.9

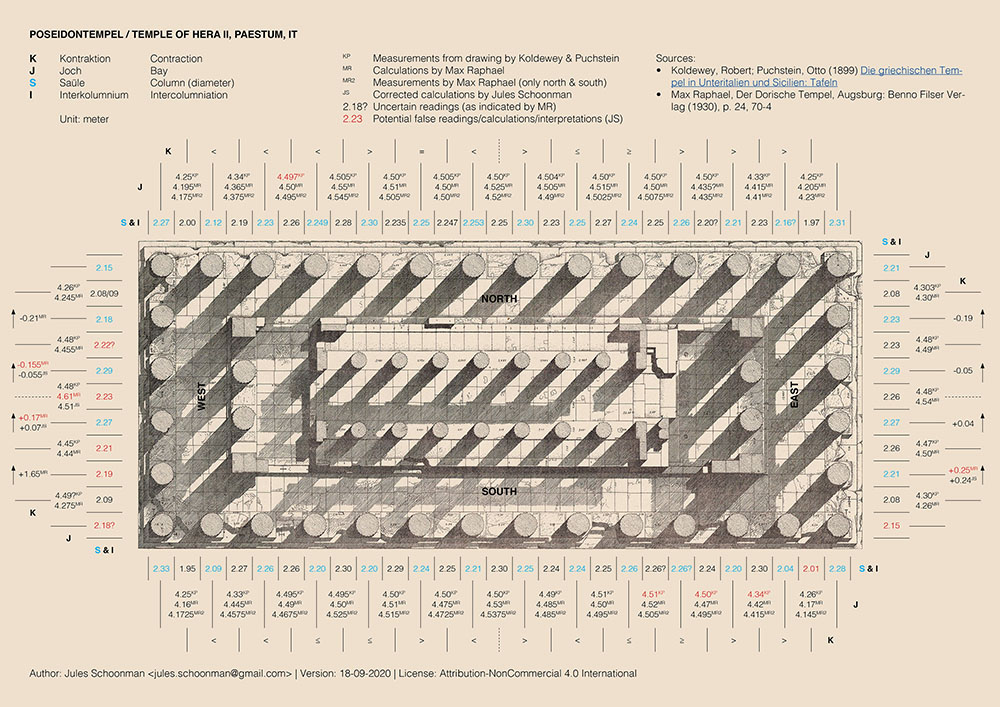

Both fronts at Paestum are differentiated when looking at the intercolumniations following the corner contractions Measurements. Their purposefulness is proven by the fact that these differences are repeated on the inner fronts [of the cella]. This is obvious in the remains at Propylon, Gaggera (Selinunt, Sicily). Subjective relativity is obtained from the point of view of the observer and limited to the contraction or stretching of the visibility of the individual columns or intercolumniation. Limitations are set by the height of the line of sight, fluctuating within the height of the capitals; by the line of approach, which coincides with either the centre axis of the front or the corner columns; by the symmetry of the fronts and the constancy of forms down to the last detail.

By changing the capitals every other column, the Christian architect relativizes the front through the diagonal view, and this again by the totally different choir view, thereby emphasising the relativism of the building by removing every chance of affirmation. The church is turned into a visible sign for something invisible. In contrast, the being of the Doric temple is sufficient in itself and for this complacency – the condition for possibility of beauty – the constancy of the whole and the parts is stressed. But that does not alter the fact that the tempel will be seen from all four sides and therefore demonstrate for each side a corresponding expression of the view, within the same visual language.

e) Articulation¶

The Doric tempel is a articulated [gegliederter] building, according to form and number.

f) Division¶

There are three main sections, which are then further subdivided: the stylobate, with the steps, the colonnade with the beams, and the pediment. The lower part normally has an odd number of steps, which almost never resemble a square or a cube. Each step is higher than an average male footstep, in other words not conceived for a light ascent.

The middle part is divided into the colonnade and the entablature. The colonnade consists of fullness and emptiness, of object and air, of light and shadow, of projection and recession, of columns and intercolumniation.

The column as a body (in contradiction to its conception as a play of forces) is a material stone body equal to an immaterial aerial body. The stone body is determined by:

- The ratio of its diameter and height, in which the number is constant, but in which in the lower and middle diameters vary;

- The height-width ratio of column and echinus;

- The number of flutings, the ratio between their width and column circumference (often determined by square number) and their own depth;

- The tapering which fluctuates between and [ = diameter].

- Whether or not entasis is used.

The duality of the articulation of column and intercolumniation is not simply juxtaposed by the Greeks. Body and air enclose one another, interpenetrate the individual column (as in the complete building, as we shall see).

This is obvious when considering the following: the perpendiculars reaching down from the abacus form a pillar made of air, while those reaching down from the upper diameter cut a cilinder in the stone column. Between those lines lie the perpendiculars of the bottom diameter, which only touch the stone column in one place, and the middle diameter, which runs half in stone and half in open air. This interweaving of stone and open air figure corresponds to that of column and intercolumniation, as the aerial border of the column is positioned in the intercolumniation while the border of the stone column is the border of the intercolumniationNeeds more explanation.

The aerial body of the column can be measured by the column height without abacus, and the width [diameter?] of the upper echinus; the stone body by the height of the shaft and the middle diameter. Looking at the relationship between the two, 12 tempels of Greater Greece fall under two proportions: and . Under a common denominator the proportions differ only a single numerator: and . A variation which frequently returns.

The entablature is split into two parts: the architrave and the frieze. The first puts together all previous parts in a single wall-like band. Although it is unarticulated, the eye knows of the structure, rhythm, which is dynamically and silently sunk down into this band and whose secret nature is only indicated at its borders: by the gutta on top and at the bottom by the change of light and shadow. The architrave lays, in order to be supported; a weight held in in the air, high activity demanding passivity. In contrast, the steps, having a similar wall-like character, lay in order to support; high passivity demanding activity. This is the principle of reversal in creation.

The next building part, the geison with its flats and hanging gutta is part of both entablature and pediment. Like in the column capital, the unified piece has a double function and the border is only drawn by discontinued profiles.

The pediment consists of three bordering profiled geisa and the indented wall.

The elements of the Doric temple are not numerous but nevertheless very differentiated. One could say: all forms are a variation of a principle. This principle is the division of the wall. It’s spatial shifting and curling up. In this way the steps, architrave, metopes, abacus, pediment and wall itself are just local projections or recessions. The column is rolled up wall, structured according to an energetic viewpoint. The triglyphs are reduced columns, unrolled to the wall plane, the gutta are little columns and the echinus is an upside down contracted column. The proof of the correctness of this view is the fact that the column circumference at least equals and often exceeds the width of an intercolumniation plus column diameter.10 Moreover the fact hat the distance between the core building and the columns is gradually decreased [in time?] until it equals or falls below the column circumference.11 And lastly, the immaterial modelling plane cutting through the entire front and lining up the columns ‘invisible-visible’.

This limitation of the diversity of forms allows for precision in proportions and a relationship between proportions and various building parts, which no other art achieved. Thus the developmental direction is to bring ever more parts to the proportion, which was originally an angle-proportion in the ground plan construction. The ratio of middle diameter to intercolumniation, from abacus to a section of the architrave between two abaci, between triglyph and metope, between the two directrices in the plan all gradually conform to this constraint.

In the subdivision of the building certain numbers are preferred: 2 columns and 1 intercolumniation are followed by 2 metopes and 3 triglyphs; each triglyph has 2 whole and 2 half cuts and 3 elevations. Furthermore above 2 columns 5 slabs with drops [mutules]; above each intercolumniation 4 viae [spaces between mutules], so that the numbers do not only increase, but first preferring square numbers, then the numbers , , , from which easily the proportion can be derived. This creates a relationship between the preferred proportion () and the number of building parts.

Important! To these numbers belong by no means the bay, i.e. the bisection of two columns and the connection of their inner half across the intercolumniation, or in other words the direct connection of parts unrelated to the whole. This is an unhistoric projection (by an historicist era) of a concept of Roman or Christian architecture onto Greek architecture - with which it has nothing in common.12

After the unity, main parts, rhythm and law of the coherence of parts have been determined, the method still needs to be outlined according to which the parts and whole are related. Contrary to the dividing (deductive) method, in which the part is determined by and dependent on the whole, and contrary to the additive method, in which the whole is composed of parts, there is no immediate connection. Rather, because both part and whole depend on the same principle and the same laws of proportion, they indirectly and voluntarily form a harmonious whole. Within this general method of concordance – which later no one understood and applied better than Leonardo da Vinci – there remains space for gradual variations, depending on whether the parts are fit within the whole without being dependent on it (Poseidontempel in Paestum); the parts relate to the whole while emphasising their juxtaposition (Concordiatempel); the parts are placed above the whole, without making the whole dependent on them (Parthenon). If one combines what has been said about the relationship between part and whole with was has been said about the relationship between principle and formal reality (what will still be expanded), one could characterise this further with sentences from presocratic philosophy, which recur in different variations: kai ek panton hen kai ex henos panta (Heraklit, Diels, Vorsokratiker 12 B 10).

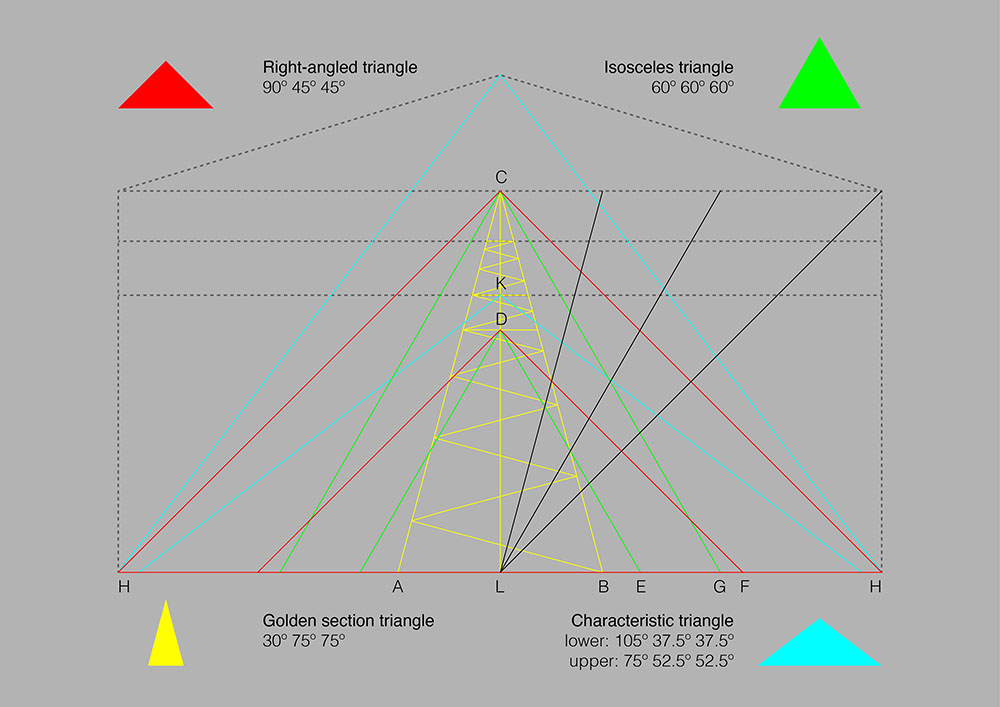

The Doric temple is a strictly implemented geometrical construction consisting of few interrelated figures, which return in different configurations in all temples.13 Because the construction of the plan also determined the spatial composition [Raumgestaltung], only the construction of the front will be elaborated in the following. Presupposing that the Greek architect has indicated the element of construction in one of the strictly geometrical figures (pediment and abacus) – in contrast to the parts which have been relieved from the strictly geometrical – one can determine the following for the Poseidontempel (Fig. 1):

One takes (on the horizontal axis of a right-angled coordinate system) in symmetrical position the distance AB between the two outer lower edges of the two middle columns and constructs the so-called ‘golden section triangle’ ABC, meaning an isosceles triangle [two sides of equal length], whose base angles measure and it top angle , its ratio therefore ; close to the golden ratio. The top touches the middle axis around the upper border of the triglyph, the sides the lower corner of the abacus. The first step of the next construction gives us the three main points of the elevation. If one draws the perpendiculars of the triangle from the corners, the 7th perpendicular determines the column shaft, the 9th the abacus top, and the 14th the height of the architrave. The number of these perpendiculars determining the elevation has a ratio of [] and [?], which determine the plan ratio of the core building and the stylobate. That such relations cannot be found in the early temples (like D and C in Selinunt) but are present in older ones (like Concordia in Akragas) proves that the development of the building proceeded in connection with, and was dependent on the plan, i.e. that the building was a adequate expression of the spacial composition.

The starting points of the determination of the irregular, free-rhythmic structuring of the plan have now been set. If one constructs on the middle axis of the elevation at the height of the shaft and triglyph border (point D and C) for each point an equilateral [sides of the same length] and a right-angled triangle (whose angles can be divided by ) one can determine the following base points on both sides of the central axis: the axis of the second intercolumniation (E), the outer border of the second column (F), the axis of the second column (G), the outer border of the corner column (H). Presuming equal strength of the columns, one can now determine the base points on the stylobat.

As a consequence of being able to construct the middle axis of the middle columns, the abacus width can be calculated, while the top width of the shaft is still missing. If one connects the central axis of the elevation at the intersection of the abacus height (K) with the base points of the outer columns, a triangle is formed whose top angle is (dividable by ) and has a ratio of to the sum of the base angles (); in other words relates to the proportion of the stereobates () and the core building (). The sides of the ‘characterising triangle’ touch the inner corners of the upper shaft of the two middle columns and thereby determine the upper diameter; in other words its tapering.

For the structuring of the triglyphs, the right angle at L, at the intersection of the axes, can be divided in . The first ray touches the outer point of the second triglyph. The second ray the axis of the second triglyph at its upper border and the third the outer corner of the upper diameter, i.e. the outer corner of the last triglyph.

In this way, all the points of the elevation have been found and the construction is complete – only the pediment is missing. Presumably this can be found by constructing an isosceles triangle over the total width of the stylobat, whose base angle amounts to so that the relationship between base and top angle is opposite to that of the ‘characterising triangle’. The perpendicular of the base angle of this ‘pediment triangle’ touches the upper fries so that now point A and B could also be found by a construction from the top of the middle axis.

Characteristic of this construction, opposed to the later ones composed with analogous elements [?] in other temples, is first the repetition of the parallel auxiliary lines and right-angled triangles at two different heights, due to which the depth distances LE and LG on the one side, and F and LH on the other are proportionally linked to the height distance CD.

Secondly the fact that between the parallel construction of regular triangles (isosceles and right-angled) an irregular triangle simultaneously cuts the central axis not in the middle but in unequal parts ( measured after the absolute size, when considering the number of perpendiculars), thereby illustrating the lively play of forces in the building, the inequality of loads and supports. This disharmonic, characteristic triangle pulls all the dramatic oppositions in its form together and refers them to the resolution in the pediment.

Thirdly in the overal view of the construction. The triangles reaching downwards from the three points in the middle axis dominate over the upward reaching triangles from the base point. This resonates with the serious, heavy and tragic overal character of the building, the place of the part in the whole! The construction is a schematic but rational image of the optical perception.

g) Arithmetic¶

Closely related to this geometric construction is the arithmetic relation, which has always been acknowledged but never depicted properly. Because science cannot get away with depicting the proportional relationships between individual parts, without graphically showing their relationship to the whole (three-dimensionally, to be precise) and the variability of the relationships. Two examples to demonstrate the limitations of Koldeweys scheme.Illustration

The comparison shows that the asserted congruence of individual parts by Puchstein immediately gets another meaning when considering their relationship to the whole. At the Poseidontempel the proportion is member of the golden section () while at the Concordiatempel each number is squared to move from the proportion which determines the details to those which determine the stylobat [depth].

SummaryThe contraction of the ‘bay’ follows a different pattern. Poseidontempel: free-rhythmic, Concorcia: strictly metric. Visual comparison of rhythm. Between the increasing sizes, decreasing inserted which are compensated by the constants.14

h) Synthesis¶

The elements of every geometric or architectural body are mathematically either plane and straight, or surface and curve. There is no doubt that the principle of planes and right angles is used, but that in the appearance regular surfaces, mostly cylinders at the column, appear. This distinction between principle (Anfang, arché) and form, appearance [Gestalt, Erscheinung] has two important consequences. The intercolumniations have the tendency to take on an opposite movement tot the column. The original immaterial plane is dissected into concave and convex oppositions, which do not loose connection with the unity of the plane. We see here what Plato has formulated as the fundamental problem of the dialectal method: how the singular and the many connect in a given number of parts [Gliedern].

The second consequence is that the imaginary planes only meet invisibly in the axes of the corner columns, while the eye perceives a curve. In this way the connection of geometrical elements is freed of the pressure of the sole geometrical sequence, in which the planes meet in straight lines and straight lines meet in a point, like in the Egyptian pyramid. The mathematical demand for a corner made place for a cylindrical body, and thereby freedom. The gap between arché and Gestalt and the freedom of being correlate closely, and both in connection to each other characterise the Doric temple. The recognition that the concave and convex has to be understood as the dissection of the principle of the plane in formal reality can also be explained from another viewpoint. In no other architecture there is such an independent distinction between the space that is inside and outside. In Indian monolithic temples the border of the volume resulted in the annihilation of the interior, and the volume seemingly became the architecture in its entirety. In the Christian church, especially in the Gothic period, the border itself was close to being abolished, to demonstrate that, regardless how thin the shell is between inside and outside, it is principally infinite and between two essentially different spaces. At the Doric temple, the building, existing of colonnades, forms a kind of equilibrium between in- and outside. We will demonstrate how the air flows into the building in a certain rhythm, flows through it. And inversely, that the front is linked to the floor plan, and that the historical development moves towards transferring even more constructional elements of the plan to the elevation, in order to create a close connection. Nevertheless to the eye the connection to the inside is loose, because the planes of the sidewalls fall in the axes of the second column (at the Poseidontempel), and from the outside the inviting banner is missing on the temple's forehead. The message is the rejecting 'know thouselves' [erkenne Dich selbst] rather than ‘come to me, all, who are laborious and burdened’ which adorns the portal of every Christian church. In this way, the colonnade becomes independent of the inner decorated space and undecorated outside. It would be principally wrong to make this relative independence absolute when claiming that the Greeks were only concerned with the plastic formation of the peristyle – and only plastic, not spatially – and that architectural imagination had operated there.15

Similar to the way in which the platonic Eros as daemon is the formal middle between the sensory-infinite and unity of the idea, between mortal and immortal, taking part in both but still being a third and independent, in this way the Doric temple is first and foremost the synthesis between the unformed outer space and the geometrically abstract plane as the ideal unity and principle of any spatiality; it is therefore formed space and despite its relative independence different from any plastic sculpture.

In summary, the Doric temple is the synthesis between the natural space and geometrical plane, i.e. its finiteness is the synthesis between the infinite depth variety of natural space and depth dimension of the abstract surface;

Its reality is the synthesis between empirical reality of natural space and the abstract-rational reality of the plane: the reality of a concrete idea;

Its structure a synthesis between lively accidental association of place and thing, and the abstract homogeneity of place and plane; i.e. it is a necessity.

In the singular, unity is expressed as synthesis of simplicity and diversity.

The ousía ek geneseos as synthesis between static and dynamic, the complete synthesis of ordered and unordered, etc. In other words: we concluded: unity as principle, dualism or better antagonism as method and form itself as result. [...].

Interplay of forces¶

Energies [Forces?] in architecture are different from other arts. They have a primary, as it were activating [verursachenden] character. It is impossible to think of them as independent. Where they are completed they appear in abstract and mechanical purity – contrary to sculpture, where they are completed when they have been freely formed out of human will and concretised in human-sensory gestures. Finally they intend a direct relationship with cosmic and metaphysical forces, without any other means of expression than mathematics and physics (to the extend that this is a theory of forces).

Important for architecture are the selection, ordening and articulation of individual forces and their combined forms. Out of pure empirical grounds, I distinguish between the following kind of energies: the spatial-functional, the material-static and psychological-expressive. The material-static include the rotating, centrifugal, centripetal, normal, trust, sloping [Neigung] and bending forces. The relation between forces are general-mechanically: action [Angriff], reaction [Ruckwirkung] (impost, Widerlager [?]) and balance; optically: visible and invisible; material: mass or ray [?] forces; aesthetically: touch, penetration, resolution (free or bound), smoothing, breaking up.

a) In the doric building, the spatial-functional energies are expressed in the relationship between front and side, between steps and pediment and in the front itself.

α) The frequent [?] change in the number of front and side columns would reveal the importance of their relationship for the spatial composition, even if it would not return in the regular width and depth proportion of the stereobat. The energies of front and side pull on [attract], or push off [reject]. Because this relationship changes with the changing standpoint of the viewer (due to for example the height of the viewpoint) it is hard to draw general conclusions without repressing the diversity of the appearance and its liveliness. Within these limitations, the following types can be discerned:

- The side escapes to the front, which escapes from the sides, etc, so that a quintessentially centrifugal type is created, which prevents any kind of fixed appearance [Gestalthaftigkeit] or dramatic tension. An example is the Paestum Basilika.

- Sides and front move toward each other. In this centripetal type, the corner column of the encounter obtains a special character; it functions as the abacus between column and entablature. It is simultaneously the most dramatic and form-fixed [Gestalthaft; inflexible] type. And these properties are even strengthened because of the secondary reversal of the energetic forces, which become primary at some viewpoints. The Poseidon temple can be named as example.

- There are many steps in between these two extreme types. At the Segesta temple, for example, the long side moves in relative fast pace to the narrower front, which itself protrudes. Here, rather than the meeting-column, the exit and final column is emphasised as bodily mass, so that the movement between fixed columns is slowed down and smoothed to a mild transition at the bend.

β) For the height, the spatial-functional energies are clearly distinguished in three layers, so that the moddeling [shaping] is both discontinuous and continuous. Discontinuous in the case of the layer by layer retreating steps and the projecting horizontal geison, which due to its slant shades its ornamentation [Trophengliederung] and enhances the illusion of depth. It is continuous in the rejuvenation and slant of the columns, due to the relationship of the decreasing width and depth of the fluting. It is often both continuous and discontinuous, like in the fluting, triglyph, etc.

The first layer is the complete foundations between the tops of the stereobat and stylobat. It builds all the subsequent layers of the tempel away from the ground, covers all the underground forces, creates a plane as smooth as glass, which rests heavily on the one hand, and is willing to take on loads on the other. The relationship between these two functions is expressed by the design of the steps, by the total and individual relations between height, width and depth. Here also variations exist between the prevailing of one of the extremes (width or height and their dramatic penetration), so that the raising of the columns is already prepared due to the bumping force with which the height dimension horizontal

[...]

Materials¶

Spatial design¶

Idea of the Doric temple¶

Appendix¶

Footnotes¶

-

After his desertion from the army and flight to Switzerland in 1917, Raphael returned to Berlin in 1920. Following Heinrich Wölfflin's refusal to accept Von Monet zu Picasso as a dissertation, Raphael was condemned to a career outside of academia, working as private teacher, writer and tour guide. From 1924 to 1932 Raphael taught at the Volkshochschule Groß-Berlin, and also briefly at the Marxistischen-Arbeiter-Schule, both newly founded institutions for adult education in the Weimar Republic. The Volkshochschule was open to adults whose previous education was limited to primary school and optional vocational training. The school did not offer re-education, but was rather aimed at workers' general formation as democratic citizens. There were no examinations or rewards in the form of certificates; most courses were set up as study groups in which students and lecturers would work together as colleagues or even friends. The socratic method was preferred, in order to entice students to develop their own critical thought and reach their own independent conclusions. The 'collective work' that Raphael alludes to, was, in other words, not the exception but the rule. The strict selection of teachers was carried by the Berlin university. They were paid 25 Reichsmark per session and worked at the Volkshochschule as a side job.

Raphael taught courses about art and philosophy at the Volkshochschule. In 1925 he lectured about Rembrandt, the next year about Degas and Corot. In a notebook entry from January 1926 he lists 'three courses, a museum guided tour and a collective meeting every two weeks' themed 'the artwork and nature as a model', 'from sketch to image', 'the development of the artist', and 'the effect of color'. In 1928 he taught two courses, and the following year one on architecture, which likely dealt with the content from Der Dorische Tempel. In a letter he mentions lectures on 'Die antike Skepsis, Die Mystik des Meister Eckart, Die Gottesbeweise des Thomas von Aquino, Die dialektische Methode bei Plato und Hegel, Philosophische Grundfragen des Marxismus'. Excursions were often part of courses, and one has to keep in mind that many of Raphael's writings started out as lectures in front of the actual works of art.

Next to the teachers Edgar Lange and Erich Rein, a community of participants formed around Raphael, with whom he also corresponded. His, in his own words, favorite student was Erna Siegel, who attended his courses in the early 1930s, and with whom he corresponded until 1952, his year of death. In February of 1952 she writes:

When I attended your courses almost exactly 20 years ago, I was completely uneducated and a blank slate (I mean this only in terms of the mind, please don't laugh). And yet, as far as I remember, I understood most of what you said.

It is a testimony to Raphael's pedagogical skills that he was able to convey the detailed analysis of Der Dorische Tempel to an audience of workers that was generally sceptic of intellectuals. When, in 1932, Raphael's course on the Die wissenschaftlichen Grundlagen des 'Kapitals' was cancelled by the Volkshochschule, Raphael had already decided to leave Berlin for Paris. ^JS ↩

-

The quote is taken from the end of Book X when Odysseus and his men leave the island Aeaea after staying there for a year in the palace of the goddess Circe. While Circe had initially cast a spell on a cohort of his men, transforming them into pigs, Odysseus is able to force Circe to break the spell with the help of Hermes, and to have her welcome him and his men. After enjoying Circe's hospitality for a year, Odysseus is reminded of his homeland and decides to set sail again. His men are in utter despair after hearing that their next destination is the underworld to consult the ghost of Teiresias, following Circe's instructions. This is when she passes by unnoticed:

The men were broken-hearted as they heard me, and threw themselves on the ground groaning and tearing their hair, but they did not mend matters by crying. When we reached the sea shore, weeping and lamenting our fate, Circe brought the ram and the ewe, and we made them fast hard by the ship. She passed through the midst of us without our knowing it, for who can see the comings and goings of a god, if the god does not wish to be seen? The Odyssey, Book 10.573, tr Samuel Butler, 1900, Perseus Digital Library

In the text VI. The Struggle to Understand Art, written in the same year as The Doric Temple and first published in The Demands of Art (1968), Raphael references the same passage when he discusses the three requirements of an active analysis of the work of art. Tracing the creative process, analysis must:

- lead from the creative work to the process of creation;

- reveal artistic creation as directed toward (1) an invidivual idea in which subjective-conditional and objective-absolute elements are combined, (2) totality (3) necessity;

- replace the world of things with a hierarchy of values (The Demands of Art, p. 190).

The third requirement, the one closest to the essence of a work of art, relates not to its subject matter (say, a painting of a historic battle or a rotten apple) but to the overall associative meaning conveyed by the intensity of its figuration, and the elimination of descrepancies between meaning and subject matter. The figuration resembles a hierarchy of values, but there's no such thing as an absolute value. This is an intrinsic limitation of creative power:

The work is neither creation ex nihilo nor imitation of the creation of the world. On the margin of what man can do there appears that which he cannot or cannot yet do–but which lies at the root of all creativeness. All great creators have felt this and have most often expressed it in religious language. When Moses wished to look upon God's glory he was told: "Thou shalt see my back parts; but my face shall not be seen." And Homer says: "And when a god wishes to remain unseen, what eye can observe his coming or his going?" (The Demands of Art, p. 197)

The motto thus expresses not only the limitations of an artistic work, but also the limitations of the investigation that follows in The Doric Temple. 'Any investigation of art must [...] recognize that its main purpose is "to have probed what is knowable and quietly to revere what is unknowable."' (The Demands of Art, p. 198; quote from Goethe: Wisdom and Experience, selected by Ludwig Curtius, tr. and ed. Hermann J. Weigand (New York, 1949), p. 94) ^JS ↩

-

I use the words realism and idealism epistemologically. ^MR ↩

-

Such a science of art is empirical insofar as it departs from the direct examination of works of art, and logical insofar as it presupposes a theory of artistic creation independent of the place and time of the origin of works of art. ^MR ↩

-

This compositional preparation of the pediment is clearly visible at the Poseidontempel, while lacking at others. ^MR ↩

-

These 12 temples were all visited and measured by me; others were studied by means of photos and reconstructions. The measurements served just as an aid to understand the artworks, not an end in itself. Better measurements are possible. The current bad state of the monuments corrupts the measurements. The measurements were compared to those of others, which led to the conclusion that the superficial measurements of Koldewey and Puchstein do not justify the dogmatic approach of their successors. ^MR ↩

-

[Table comparing the depth and width of the Stylobat of 12 temples to the height of the columns.] ^MR

Group I Depth of Stylobat Width of Stylobat Height of columns Basilica 54•28 24•52 6•48 -

genesis eis ousian - Schöpfung gemaß der Substanz. ousia ist die erste der zehn aristotelischen Kategorien. Raphael hatte wahrscheinlich »Wesensschöpfung« übersetzt. ^WA ↩

-

SummaryThese assertions counter the measurements of Koldewey. Multiple centimeters in the case of Segesta. Criticises measurements of Puchstein and Koldewey. There is a rhythmic contraction, not simply a metric one. P. and K. interpret the building to fit their hypothesis: everything else is a deviation. Everything can be averaged with maths. The bays are miscalculated. The average is not present in the actual temple. It is methodically impossible to speak of uniform dimension and inaccuracies. It’s not that there is no average or norm, but these are underlying principles, the backbones for the development of the dimensions, not their concrete reality. Their realisation is not based on technical inaccuracies but on the principle of free rhythm, which is varied at each interval with the aim to develop multiple solutions to the same challenge, to relate and interpenetrate row and symmetry. ^MR ↩

-

[Table indicating that no intercolumniation nor bay exceeds the column circumference.] ^MR ↩

-

In the later Juno, Poseidon and Concordia temples, the east and largest pteron [distance between columns and cella] is less than the middle column circumference. The same for Temple C – wrongly dated by Koldewey and Puchstein. In the case of the Basilica, Ceres, Tempels A and E, the pteron more or less equals the lower column circumference. Only the early Temples D, F and the Herculestempel have a pteron which is larger than the circumference. ^MR ↩

-

‘Bay’ and 'column + intercolumniation' both originate from the wall, but have developed differently out of it and have a different relationship to it. In the Christian church, the void grows out of an interruption of the otherwise intact wall and it remains subordinate to it as a tangible non-being. The pillar, in contrast, is a projecting part of the wall and superordinate to it. In the Doric temple, the void grows out of the subdivision and rotation of the wall. To the extent that column and intercolumniation become real (the void is the being of the non-being), they become independent and the original wall disappears into an imaginary modelling plane. The (Christian) bay grows out of a transcendent principle and the trinity of wall, pillar and void results in the brick [aufgemauerte] architecture.

In brick architecture, the bay is characterised by a contrast between load-bearing and supported parts, between wall and pillar - a dualism completely at odds with Doric architecture. The load-bearing and supported forces are decomposable in principle. On the one hand, because of this, the pillar is just a bundle of directional forces [Kraftstrahlen], whose formal coherence is only external. On the other hand, the decomposition of the total force in partial forces determines the bay.

The decomposition of the column goes against the Greek spirit, because its bodily form is the synthesis of opposites. The architect of the Doric temple admittedly works with multiple bearers, but the load is one and thereby chains together the separate bearers. The Greek has a unity of force and form, the Christian a dualism.

In the bay of the Christian church a total different relationship exists between the dimensions, and a different relationship to the total space. Here, width dominates; there depth. The single bay [in the Christian Church] is inferior to the depth-movement of the space as a whole, despite having an elaborate and diverse formal language [Formensprache]. Column and intercolumniation [in the Doric Temple] are not inferior to the total width of the front; their spatial function does not exceed their formal presence [formales Sein] – contrary to the discrepancy in the Christian church. In the church, the arcade supports are primarily lonely as individual; its procession, tied together by a transcendental force, is an arranged row, in which the dynamic principle of connecting one support to the next is infinite. The ancient row of columns, of which each member is social despite its individuality, is the juxtaposition of singularities in a primarily defined and finite cube. ^MR ↩

-

[Referral to Anhang.] ^MR ↩

-

[Referral to footnote 5. Koldewey praised the 'academic' Concordia temple.] ^MR ↩

-

Important [5 pages about the difference between plastic and architectural bodies. In short: architecture is based on the expression of forces; sculpture on the human body.] ^MR ↩